Changing of the Guard

Changing of the Guard Clear and Present Danger

Clear and Present Danger Hounds of Rome

Hounds of Rome Breaking Point

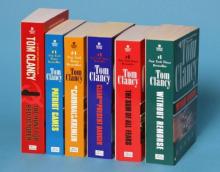

Breaking Point Tom Clancy's Jack Ryan Books 7-12

Tom Clancy's Jack Ryan Books 7-12 Full Force and Effect

Full Force and Effect The Archimedes Effect

The Archimedes Effect Combat Ops

Combat Ops Into the Storm: On the Ground in Iraq

Into the Storm: On the Ground in Iraq Under Fire

Under Fire Point of Impact

Point of Impact Red Rabbit

Red Rabbit Rainbow Six

Rainbow Six The Hunt for Red October

The Hunt for Red October The Teeth of the Tiger

The Teeth of the Tiger Conviction (2009)

Conviction (2009) Battle Ready

Battle Ready Patriot Games

Patriot Games The Sum of All Fears

The Sum of All Fears Fallout (2007)

Fallout (2007) Red Storm Rising

Red Storm Rising The Cardinal of the Kremlin

The Cardinal of the Kremlin Executive Orders

Executive Orders Lincoln, the unknown

Lincoln, the unknown Threat Vector

Threat Vector The Hunted

The Hunted Shadow Warriors: Inside the Special Forces

Shadow Warriors: Inside the Special Forces End Game

End Game Special Forces: A Guided Tour of U.S. Army Special Forces

Special Forces: A Guided Tour of U.S. Army Special Forces Locked On

Locked On Line of Sight

Line of Sight Tom Clancy Enemy Contact - Mike Maden

Tom Clancy Enemy Contact - Mike Maden Fighter Wing: A Guided Tour of an Air Force Combat Wing

Fighter Wing: A Guided Tour of an Air Force Combat Wing Springboard

Springboard Line of Sight - Mike Maden

Line of Sight - Mike Maden EndWar

EndWar Dead or Alive

Dead or Alive Tom Clancy Support and Defend

Tom Clancy Support and Defend Checkmate

Checkmate Command Authority

Command Authority Carrier: A Guided Tour of an Aircraft Carrier

Carrier: A Guided Tour of an Aircraft Carrier Blacklist Aftermath

Blacklist Aftermath Marine: A Guided Tour of a Marine Expeditionary Unit

Marine: A Guided Tour of a Marine Expeditionary Unit Commander-In-Chief

Commander-In-Chief Armored Cav: A Guided Tour of an Armored Cavalry Regiment

Armored Cav: A Guided Tour of an Armored Cavalry Regiment Tom Clancy's Jack Ryan Books 1-6

Tom Clancy's Jack Ryan Books 1-6 The Ultimate Escape

The Ultimate Escape Airborne: A Guided Tour of an Airborne Task Force

Airborne: A Guided Tour of an Airborne Task Force Debt of Honor

Debt of Honor Cyberspy

Cyberspy Point of Contact

Point of Contact Operation Barracuda (2005)

Operation Barracuda (2005) Choke Point

Choke Point Power and Empire

Power and Empire Every Man a Tiger: The Gulf War Air Campaign

Every Man a Tiger: The Gulf War Air Campaign Endgame (1998)

Endgame (1998) EndWar: The Missing

EndWar: The Missing Splinter Cell (2004)

Splinter Cell (2004) The Great Race

The Great Race True Faith and Allegiance

True Faith and Allegiance Deathworld

Deathworld Ghost Recon (2008)

Ghost Recon (2008) Duel Identity

Duel Identity Line of Control o-8

Line of Control o-8 The Hunt for Red October jr-3

The Hunt for Red October jr-3 Hidden Agendas nf-2

Hidden Agendas nf-2 Acts of War oc-4

Acts of War oc-4 Ruthless.Com pp-2

Ruthless.Com pp-2 Night Moves

Night Moves The Hounds of Rome - Mystery of a Fugitive Priest

The Hounds of Rome - Mystery of a Fugitive Priest Into the Storm: On the Ground in Iraq sic-1

Into the Storm: On the Ground in Iraq sic-1 Threat Vector jrj-4

Threat Vector jrj-4 Combat Ops gr-2

Combat Ops gr-2 Virtual Vandals nfe-1

Virtual Vandals nfe-1 Runaways nfe-16

Runaways nfe-16 Marine: A Guided Tour of a Marine Expeditionary Unit tcml-4

Marine: A Guided Tour of a Marine Expeditionary Unit tcml-4 Shadow Warriors: Inside the Special Forces sic-3

Shadow Warriors: Inside the Special Forces sic-3 Jack Ryan Books 1-6

Jack Ryan Books 1-6 Cold Case nfe-15

Cold Case nfe-15 Changing of the Guard nf-8

Changing of the Guard nf-8 Splinter Cell sc-1

Splinter Cell sc-1 Battle Ready sic-4

Battle Ready sic-4 The Bear and the Dragon jrao-11

The Bear and the Dragon jrao-11 Fighter Wing: A Guided Tour of an Air Force Combat Wing tcml-3

Fighter Wing: A Guided Tour of an Air Force Combat Wing tcml-3 Patriot Games jr-1

Patriot Games jr-1 Jack Ryan Books 7-12

Jack Ryan Books 7-12 Mission of Honor o-9

Mission of Honor o-9 Private Lives nfe-9

Private Lives nfe-9 Operation Barracuda sc-2

Operation Barracuda sc-2 Cold War pp-5

Cold War pp-5 Point of Impact nf-5

Point of Impact nf-5 Red Rabbit jr-9

Red Rabbit jr-9 The Deadliest Game nfe-2

The Deadliest Game nfe-2 Springboard nf-9

Springboard nf-9 Safe House nfe-10

Safe House nfe-10 EndWar e-1

EndWar e-1 Duel Identity nfe-12

Duel Identity nfe-12 Deathworld nfe-13

Deathworld nfe-13 Politika pp-1

Politika pp-1 Rainbow Six jr-9

Rainbow Six jr-9 Tom Clancy's Power Plays 1 - 4

Tom Clancy's Power Plays 1 - 4 Endgame sc-6

Endgame sc-6 Executive Orders jr-7

Executive Orders jr-7 Net Force nf-1

Net Force nf-1 Call to Treason o-11

Call to Treason o-11 Locked On jrj-3

Locked On jrj-3 Against All Enemies

Against All Enemies The Sum of All Fears jr-7

The Sum of All Fears jr-7 Sea of Fire o-10

Sea of Fire o-10 Fallout sc-4

Fallout sc-4 Balance of Power o-5

Balance of Power o-5 Shadow Watch pp-3

Shadow Watch pp-3 State of War nf-7

State of War nf-7 Wild Card pp-8

Wild Card pp-8 Games of State o-3

Games of State o-3 Death Match nfe-18

Death Match nfe-18 Against All Enemies mm-1

Against All Enemies mm-1 Every Man a Tiger: The Gulf War Air Campaign sic-2

Every Man a Tiger: The Gulf War Air Campaign sic-2 Cybernation nf-6

Cybernation nf-6 Support and Defend

Support and Defend Night Moves nf-3

Night Moves nf-3 SSN

SSN Cutting Edge pp-6

Cutting Edge pp-6 The Cardinal of the Kremlin jrao-5

The Cardinal of the Kremlin jrao-5 War of Eagles o-12

War of Eagles o-12 Op-Center o-1

Op-Center o-1 Mirror Image o-2

Mirror Image o-2 The Archimedes Effect nf-10

The Archimedes Effect nf-10 Teeth of the Tiger jrj-1

Teeth of the Tiger jrj-1 Bio-Strike pp-4

Bio-Strike pp-4 State of Siege o-6

State of Siege o-6 Debt of Honor jr-6

Debt of Honor jr-6 Zero Hour pp-7

Zero Hour pp-7 Ghost Recon gr-1

Ghost Recon gr-1 Command Authority jr-10

Command Authority jr-10 Tom Clancy's Power Plays 5 - 8

Tom Clancy's Power Plays 5 - 8 Checkmate sc-3

Checkmate sc-3 Breaking Point nf-4

Breaking Point nf-4 Gameprey nfe-11

Gameprey nfe-11 The Hunted e-2

The Hunted e-2 Hidden Agendas

Hidden Agendas Divide and Conquer o-7

Divide and Conquer o-7